CHAPTER THREE

THE PROBLEM OF THE LIFELESSNESS

OF PEDAGOGICAL ESSENCES, THEIR VIABILITY

AND THEIR ENLIVENMENT

W. A. Landman

1.

INTRODUCTION

In a previous publication the following

fundamental axiom was stated [in Afrikaans] that is related to the problems in

the title of this chapter: "A Christian-Protestant pedagogician who

accepts the essences of educating as essences-for-himself feels called to

actualize these essences in his educative work. However, in this regard, there is a particular precondition that

has to be fulfilled before they can be actualized. Something specific needs to be recognized, namely there has to be

an enlivenment [awakening-of-life]

of the essences of educating that are characterized by their lifelessness, but also by their viability. Because of their viability, their lifelessness can be transformed

into enlivenment. The essences of a philosophy of life serve as

enlivening contents for the essences

of educating."(1)

It is now necessary to take a closer look

at this matter. One way to do this is

to make a study of phenomenological analyses of the category "life"

in order to try to determine what light is shed on the meaning of

"lifelessness", "vitality", and "enlivenment". But first the following remarks:

When it is said that a pedagogical essence is

lifeless but yet is viable, suddenly it becomes clear that such an essence is

not lifeless in the same way as is, e.g., a stone. A stone is lifeless and will remain so since it is not viable. On the other hand, an essence is viable and

thus its lifelessness in reality is typified as latent enlivenment. This

means that with a pedagogical essence there is life that remains concealed,

dormant and invisible(2) until something

particular happens. Latent living

essences really become living essences when their latent but present life is

awakened, thus when the act of awakening [the essence]-to-life is

actualized. In this regard particular

philosophy of life essences serve as the means for doing this. For example, through intermediate Christian-Protestant

[philosophy of life] essences a particular educator actually brings to life for

himself particular pedagogical essences: real enlivenment is brought about with

the help of life giving (life awakening) contents (essences). In light of what has just been discussed it

also is clear why there is mention of life awakening

activities and not of life begetting

activities. Here no new life is created

but already existing life is awakened, activated. Pedagogical essences, then, become particular acts (activities).

It also is because of this latent

enlivenment of the pedagogical essences that it is possible to implement the

"methods of a pedagogical perspective"(3) in order to expand our knowledge of education. These methods imply that each of the manifested

pedagogical essences are accepted and that there is a purposeful and thoughtful

search for their life philosophy-essences in life philosophy sources. Each essence that in this way is accepted

then serves as a light (perspective) which is cast on the mentioned sources;

this is an action that decidedly would be impossible if a non-living

lifelessness should be replaced by its real meaning, namely latent living. The latent enlivenment of the pedagogical

essences then become really enlivened because of the philosophy of life

perspective applied to them. The use of

an essence is a particular awakening-of-life activity.

Above, two enlivening activities are

described which can be called a life

philosophy enlivenment and an epistemological

enlivenment. (Another form of

epistemological enlivenment is when an essence is used categorically.)(4) In the following pages

attention is given to the possibility of

the former that already appears as a possibility from the name "philosophy

of life", when it is viewed as a living

philosophy--a philosophy that has particular connections with a person's

way of life.(5)

2.

SOME ANALYSES OF THE PHENOMENON "LIFE"

(a)

Gerd Brand: A person's living being-in-the-world is

a being-directed and being directed is movement. It is a living movement, a movement of life that is lived in

various ways. It is a living movement

that takes place, that occurs. Life

then is an event of movement by which a person is carried, by which progress is

possible, and by which something becomes useful.(6) Pedagogical essences then

have a latent enlivenment because of their characteristics of: (i) being-directed: There is mention of

a possible being-directed to the actualization of other pedagogical essences and

a possible being-directed to attaining the aims of educating; (ii) living movement: There is mention

of possible dialectical-hermeneutic actualized movements as living progress;(7) (iii) movement that occurs: educating

is a possible occurrence when adults and children are involved with each other and

decidedly is not process-like in nature.(8)

Because of being-directed, living movement

and movement that occurs, pedagogical essences are available as usable

possibilities in pedagogic situations.

When these three characteristics are realized in practice, latent

enlivenment has become functioning enlivenment. This is all possible because the pedagogical essences can be made

viable, thus because of the essence's giving direction, living movement and

whose movement that occurs is susceptible to the life-awakening influence of

particular life-philosophy essences

(contents).(9)

(b)

Edmund Husserl: In the life world everything is actualization and activity. What is exercised in functioning really can

be described as motivation. Among a

person, the world and other persons there are motivating relations in the sense

that a person is motivated to pay attention to others, to take a stand, to act

practically, to evaluate, etc.(10)

To live implies coming into function

(activity) in the form of attending, taking a stand, thinking, putting to

practice, evaluating, etc. In this

light it can be said that the mentioned ways of functioning are latently

present in real pedagogical essences, that their viability indicates that these

forms can function in relation to the essences and thus can become living

essences. Awakening-to-life by being

functional (in any way at all) leads to enlivenment. The philosophy of life is a particular instance of letting the

essence function since it is life-awakening because of its life-giving

contents.

In the practice of educating, attention has

to be given to the pedagogical essences because educating is actualizing these

essences; a position has to be taken with respect to the essences because a

choice has to be made for them and

against their contradictions and also a choice has to be made among them. There has to be a reflection on the essences.

In this regard, the following deserves consideration.(11)

Today it is generally accepted that there

are a number of possible perspectives on the reality of education. The aim of each perspective is to make a

contribution to an understanding of what educating really is and/or to its

improvement.

Questions that now are attended to are:

What possible perspectives are there and what should they be called? The following are presented for

consideration without claiming that the last word now is being said about the

matter or that there are not other valid possibilities:

There are a variety of adults who in one

way or another involve themselves with educative work, whether it is to perform

it, to think about it or both:

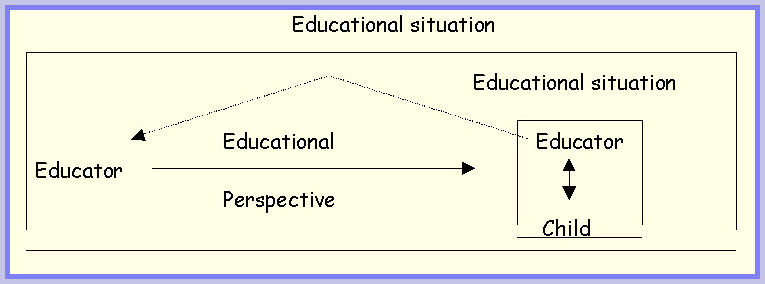

(i) In the first place there are those who,

on the basis of their educatorship (e.g., parents), are engaged in it and also

who reflect on the educative

activities that they are going to carry out or will yet exercise. They are educators who interact with children in educational situations and who reflect on this being together. In other words, they have their particular

perspective on the event of educating that can be called an educational perspective (i.e., an

educator's perspective). The educator

thinks about his educative activities with the children with the aim of

evaluating, improving, planning them, etc.

SCHEMATIC REPRESENTATION

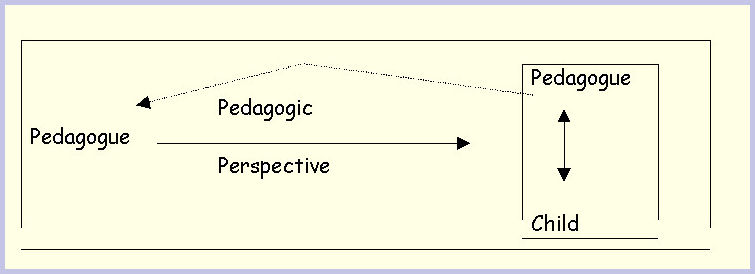

(ii) another group of educators are

"experts" because of their

particular training in Pedagogics. They can be called pedagogues who interact with children in pedagogic situations and

who can reflect in expert ways on

the educative activities they engage in with children. In other words, they have an expert

perspective on the educative event, which can be called a pedagogic perspective (i.e., a pedagogue's perspective). The pedagogue thinks in expert ways about

his educative activities with the child in order to evaluate, improve and plan

them, etc.

SCHEMATIC REPRESENTATION

Pedagogic

Situation

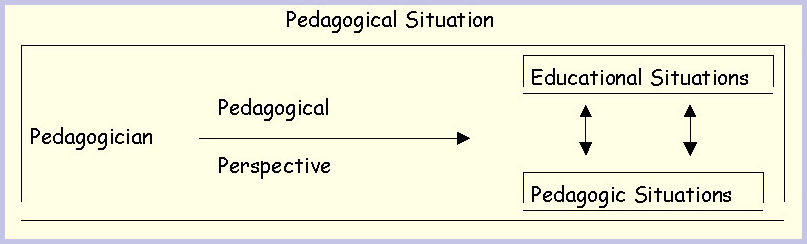

(iii) A third group of persons

distinguishable are those who in scientifically

accountable ways investigate educational and pedagogic situations in order

to disclose real essences, their sense and meaningful relations with the aim of

their being noted by pedagogues and giving guidance to educators. They are the pedagogicians who in pedagogical

situations focus scientific research on the phenomenon of educating which,

as an educative event, shows itself in educational and pedagogic situations. In other words, they have a scientific

perspective on the event of educating that can be called a pedagogical perspective (i.e., a pedagogician's perspective). The pedagogician thinks about educational

and pedagogic situations with the aim of understanding them ontologically.

SCHEMATIC REPRESENTATION

Thus, there is mention of:

(i) a (non-expert)

educational perspective;

(ii) a (expert) pedagogic perspective;

(iii) a (scientific) pedagogical

perspective.

A particularly relevant question now is

with which are the different part disciplines of pedagogics involved in their

scientific practice?

(i) Certainly not with an educational perspective because the

practitioners and authorities of these disciplines possess expert knowledge of the event of

educating;

(ii) also not with a pedagogic perspective because they are not merely involved in

applying their expertise in the child's interest;

(iii) but indeed with a pedagogical perspective because each

part-discipline has the task of the ontological understanding of the event of

educating from its own perspective.

Thus, each has to overcome essence blindness and disclose real pedagogic

essences with their sense and meaningful relations.

This view implies that there are various

part-disciplines of Pedagogics that involve themselves with a pedagogical perspective on educative

activities. Consequently, there is

mention of a sociopedagogician's using the pedagogical perspective: a

sociopedagogician implements the pedagogical perspective in sociopedagogical

ways and then there is mention of a sociopedagogical perspective. For the same reason there is a

psychopedagogical perspective, a didactic pedagogical perspective, etc.

Is there also mention of a sociopedagogic,

a psychopedagogic, a didactic pedagogic perspective? Yes, to the extent that a pedagogue

evaluates, plans, etc. his educative activities with a child in the light of

his expert knowledge of sociopedagogics, psychopedagogics, etc. Here, however, a science (sociopedagogical,

psychopedagogical, etc.) is not involved as such but there is use of sociopedagogical, etc. findings in practice.

(c)

Martin Heidegger: that which is alive moves and a

fundamental way of moving is not merely changing position but action as

considered progression and breaking through.(12) The way of actualizing a

pedagogical essence (or group of essences) after another is one of considered progression

since this way is thoughtfully actualized.

There is a (dialectic) reflection on the most purposeful way of

actualizing them and which ways ought to be followed. For example, it is determined that the direct way from pedagogic

Association to Engagement is an impoverished way while this way via pedagogic

Encounter is the most pedagogically accountable one.(13) In addition, there is

mention of breaking through. Pedagogic

association is broken through when because, e.g., of an intensification of the

actualization of the pedagogic relationship structures there is a movement to

pedagogic encounter.(14)

Thus, with essence actualization there is

mention of progression and breaking through, thus of life. Each essence is a possibility of progression

and breaking through, i.e., it is latent enlivenment. When the progression and breaking through are actualized, latent

enlivenment becomes actualized. This

progression and breaking through occurs in concrete (particular) educative

situations, i.e., in situations in which a philosophy of life is summonsed to

the progression and breaking through.(15)

(d)

Hans-Georg Gadamer: The life of a person is manifested in his lived experiences. This means there is a connection between

life and lived experiencing and this relation is the particular connection

between lived experiencing and life: moments of lived experiencing are moments

of the event of living itself that allow life to be in its tangible scope and

vigor. Because lived experiencing is

itself embedded in the totality of life, the totality of life also is present

in it.(16) When real pedagogical essences now are seen as able to be lived

experienced(17) this means that the following

characteristic can be attributed to them: pedagogical essences are particular moments

that the event of educating allows to live.

Naturally, the precondition is that their latent enlivenment, thus the

possibility of letting the event of educating live, has to be awakened to

authentic enlivenment by implementing a life-giving philosophy of life. Pedagogical essences are possibilities that

awaken life in the event of educating, provided they even are made living by

life philosophy contents--a person lives from contents and to be living is to

have a relationship with contents.(18) A living educative event is

one in which living pedagogical essences are actualized in their relationships in

a particular way, namely, in a dialectic-hermeneutic way as living as well as

life awakening movement. In this way

the educator can support a child to enter into and lived experience the

pedagogical essences with their life philosophy contents.

(e)

M. De Tollenaere: The term "presence" often has a more dynamic and richer

meaning than the terms "now" and "the present" since it

clearly expresses the deep breadth of relationships among persons and of living. The living that brings the mere "now" of something to

presence is its being (its being

there and being such-and-such in its fullness--W. A. L.) that is discernible as

an occurrence-in-function. Living as a

functioning occurrence shows that which is hidden in human existence, thus

brings it to presence. This living as

presence is characterized by a rhythm of change: an activity is exercised and

undergone; there is mention of creating and experiencing something, awakening

and resting, of interrupting and building up, of coming and going.(20) Now when pedagogical essences

are described as latent enlivenment, in light of the above, this means that

they possess the following actualizable characteristics:

(i) The educator can allow them to be,

i.e., he can put them in the present in their fullness. This is precisely what occurs in pedagogic

situations and therefore it also is possible to notice pedagogic essences;(21)

(ii) The educator can allow the essences to

occur. E.g., by noticing the

objectionable the experience of opposition arises and after this opposition new

ways of living are presented, etc.;(22) the essences become functional;

(iii) Pedagogic essence that live in

reality are activities that are carried

out. Thus, they are actions. Hence, e.g., there is mention of activities

of trust that make encountering activities possible, of activities of authority

which underlie activities of intervening, of activities of understanding that

allow activities of agreement to progress meaningfully, etc. These activities also are undergone by the participants in the

pedagogic event in the sense that they are embraced by them and consequently

they are summonsed to actualize them;

(iv) Pedagogical essences live because they

can be brought forth, i.e., can appear, can be awakened and then come to

rest. An awakened pedagogic association leads to actualizing the

pedagogic encounter and then comes to rest.

This does not mean that its essences are switched off but that they

tentatively are not observable. The

observable becomes unobservable (see interrupted) and if necessary the

unobservable again becomes observable (see built up). The enlivenment of pedagogical essences then appears in the rhythm

of their presence, a rhythm that is co-dependent on the life-awakening effect

of a philosophy of life, which also is dialectic in nature. Dialectic rhythm is evidence of enlivenment

and enlivenment shows itself as dialectic rhythm.

(f)

Nicolai Hartmann:

Actual human life is filled with values and, consequently, a person

continually works at disclosing and realizing values. Human life is characterized by an awareness of values. Therefore, it is possible to see life as values. Life is not created

by persons but it exists, it is real, it is given to him as valuable and

entrusted to his care. Among other

things, here care refers to a choice for

particular values, thus for taking a position in favor of them. Care as a choice for a positive position

refers further to a becoming aware of the demanding nature of the valuable as a

matter of propriety.(23)

If "life" now is to be attributed

to pedagogical essences, one has to be able to show that these essences are

pedagogically valuable, i.e., that they are what have to be actualized if the

child is to progress on his way to proper adulthood. If the contradictions of, e.g., the experience of security,

gratitude for this experience, security because of acceptance, loving presence

and personal initiative are conducive to becoming a proper adult, the presence

of these essences of gratitude for pedagogic security(24) are worthless. Each of

these essences serve as preconditions for actualizing other essences and thus

are necessary for progressing on the way to proper adulthood. For example, with the absence of the

experience of security, anxiety arises and the pedagogic experience indicates

that anxiety is anti-essence actualizing.

The educator has to choose(25) in favor of particular living pedagogic essences, namely, for that

which really is made living by his particular philosophy of life. Latent living in this sense means that an

essence is available as a possible choice; thus it is one of the possibilities

that the educator can chose to actualize:

Life susceptibility will then mean susceptible to life because of

choice, thus for actual enlivenment because it is chosen and then this

enlivenment speaks in the form of a view and demand--the pedagogic essences

have become particular demands of propriety.

Because of his being a person the educator

has at his disposal a valuing consciousness, i.e., an inherent conception of

values. This means that he is aware

that he can and must value (judge).

While he expresses value judgments he becomes aware that certain matters

are more valuable to him than others.

Thus, educating his children by him is appraised as valuable and child

neglect as not valuable. He appraises

in terms of contrasts such as educating as value

and neglect as not valuable. This

means that for him educating is acknowledged as elevated above neglect. He then is aware of the valuableness of

educating and also is seized and claimed by educating-as-a-value. Educative work as a matter of living now

places demands on him and indeed the

demand to properly actualize the

pedagogic relationship, sequence, activity and aim structures. These structures then are seen as demands of

propriety. This means that if he will properly educate he has to fulfill the demand that these structures have to be

actualized and this means that the following have to be clear to him:

the relationship of understanding as value,

the relationship of trust as value,

the relationship of authority as value,

association as value,

encounter as value,

engagement as value,

intervention as value,

return to association as value,

periodic breaking away as value,

educative aims as value,

pedagogic activities as valued and their contrasts as not valued.

The educator is aware that in valuing his

educative work he has to judge whether these educative values are actualized by

him. This means that these values are yardsticks (criteria) for determining

whether the educative work is performed properly. Then these values have become norms.(26) The pedagogical structures mentioned now are

for the educator an indication of what ought to occur, thus what has to be

lived in his educative work. As norms

these structures are direction-indicating for him especially in the sense that

he knows that what for him are valuable in reality are demands for propriety

(norms) to which he has to show unconditional obedience. This is the case because as far as the

accepted norms (educative values as demands of propriety) are concerned, they

are not open to choice since they are mandates

for him. If he does not accept

these demands of propriety (norms) as mandates

he cannot be an educator who acts in pedagogically accountable(27) ways. The mandate is that

these norms have to be obeyed. This

occurs when the educator accepts the mentioned educative values as matters that

have to be actualized and when he judges the quality of his educative work in

their light.

The mentioned educative values are valuable

for all living(28) educative situations and thus the

norms flowing from them are valid for all educative work that is

practiced. However, each educator is in

a particular educative situation in which a particular philosophy of life

speaks. This means that the universally

valid norms have to be filled with particular life-view contents (e.g., Christian-National),

thus they have to be made living. When

this occurs these norms become principles

for a particular educator. Then they

become rules of behavior that are direction-giving for his actions with

particular children (e.g., children of the Covenant).

FOR EXAMPLE

The relationship of understanding, as value, is normative (demand posing) in the form of understanding

being-a-child and understanding the demands of propriety that, in their turn

become the following principles in

concrete educative situations: Understanding the significance and implications

of being a child of the Covenant, and of Protestant-Christian demands of

propriety.

(g)

Heinrich Rombach: Movement is the presence of life.

Only in an ontological respect can there be a distinction between rest

and movement since they are only present with each other. In an ontological sphere, both are

synthesizable so that movement can be "calm" and rest can be

"lively". This means that a

structure can be described as ""lively-rest". Lively rest indicates that the structure

lives and thus is not a substance but an event. In this sense, life is a category with ontological status. Thus, life is not an abstraction or absolute

power but is the result of enlivenment; that is, enlivenment shows itself as

life. The enlivened structure lives. Life is a phenomenon noticeable in all

structures and gives each its particular nature. Living structures are authentic preconditions for a person's

becoming and in this sense enlivenment can be used as a criterion. What is the

quality of the enlivened life of the structures? What kind of enlivening is there of the structures? Enlivening means that structures are

activated such that actions can immediately occur in their light.(29) These are actions that are

possible because the educator is present in each structure as a person.(30)

Fundamental pedagogical structures (with

their essences) are viable because they are particular events that can be

brought to lively rest. Calm lingers by

a structure (e.g., the relationship of trust) and then it is possible to move

meaningfully to another structure (e.g., the relationship of authority) by

which there is a lingering until additional meaningful movement has become

possible. However, such movement

requires enlivenment and a philosophy of life, as life awakening action, enters

the foreground. Now when enlivenment is

applied as a criterion, questions such as the following become relevant: What

is the quality of an educator's philosophy of life knowledge? Does he succeed in realizing and integrating

life philosophical knowledge that is relevant at a particular point of time?,

etc.

3.

SOME METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In the previous pages in terms of some

phenomenological analyses of the phenomenon "life" an attempt was

made to reflect on and describe lifelessness, viability and enlivenment (awaken

life) as characteristic of fundamental pedagogical structures (with their

essences and meaningful relations). The

un-naive practitioner of Pedagogics now asks the following epistemological

question: On what ground is such

reflection possible? Answer: on the

basis of the fact that the reflector (Pedagogician) is by the event that has to be thought about. Reflecting (as phenomenological analysis) is

possible because it bridges the empiricistic, idealistic and "ism"

estrangement from the to be reflected on reality. Briefly, the pedagogician's being-in-the-world makes possible his

reflecting and the resulting understanding.

Viewed epistemologically the

pedagogician lays down his own being-in-the-world as the first precondition for his reflecting. In other words, he poses being-in-the-world as an ontological

category, thus as a light that makes further illumination possible. Only then is the following question

meaningful: Which point of departure

is possible because of my thinking being-in-the-world? Answer: the reality that I have selected to

think about is the meaningful point of departure.

Thus:

(i) the first precondition for thinking is the

thinker's being-in-the-world (ontological category); (ii) the point of

departure for thinking that now is possible is an aspect of reality itself.

The point of departure for pedagogical

thinking is not the ontological category but the reality of educating itself as

it is rooted in the life world (as a particular aspect of reality). The

ontological category refers to the first precondition that has to be satisfied

in order to make the mentioned point of departure possible.

In addition, it is the rootedness

(embeddedness, foundedness) of the reality of educating in the life world

itself that makes possible the approach followed in this chapter, namely, to

first inquire into the anthropological meaning

of the phenomenon "life" and then to determine its pedagogic significance. This is possible because pedagogical thinking

is a particular form of anthropological thinking. In his particular way, a pedagogue is an anthropologist.

He asks particular anthropological questions from an autonomous

pedagogical perspective.

4.

PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE ESSENCES AS CONTENT

Lifeless (latent living) pedagogical essences become alive on the basis of

their viability and enlivenment by life philosophy contents (essences). From this fundamental axiom that emanates

from the previous pages it now can be deduced that it will be meaningful to

give close attention to two pronouncements given about "content".

(a)

Viktor Warnach: An unbiased phenomenological

analysis clearly shows that each being has two fundamental moments not

reducible to but associated with each other: an assimilation-holding and a

content moment. The holding moment is

receptive to content that has a particular function.(31) For example, a relationship of trust with pedagogic content will limit that relationship to a pedagogic

situation. Then there is mention of a

pedagogic relationship of trust. The

pedagogic relationship of trust can be further limited by Christian content to a Christian situation of

educating. For the educator, knowledge

of content thus is of particular significance paired with knowledge of the

holder of or structure (essences) of this particular content.

The holder (structure with which the

educator as person is present) seeks fulfillment (actualization) and it is the

ontological function of the content to bring about this actualization.(32) Pedagogic content makes actualization

possible in pedagogic situations and life philosophy enlivenment of the content

makes actualization possible in particular pedagogic and educative

situations. Once again knowledge of

content is assumed.

(b)

Leo Gabriel: Content is expressed in a form such

that the form is a primary constituent of the content. This means, for example, that philosophy of

life contents (with which the educator as person is present) seeks fulfillment

(actualization) and it is the ontological function of the form to bring this

actualization about. Thus, the

following contents seek fulfillment in the form (structure) known as a

pedagogic04:58 PM 2007/01/14 relationship of trust: "And who so shall receive one such little

child in my name receiveth me. (Matt. 18:5)". "... we and our children ... that You have accepted us and our children as Your children"

(Baptismal vows); "For thus saith the Lord God, the Holy One of Israel; In

returning and rest shall ye be saved; in quietness and in confidence shall be

your strength. (Is. 30:15)".

The unity of the reciprocal implications of

form and content is corroborated in these two pronouncements. According to Warnach, form is in search of

content. Gabriel indicates that content

is in search of form. As a synthesis,

it can be said that form and content are in search of each other.

5. REFERENCES

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., Fundamentele Pedagogiek en die Opvoedingswerklikheid, 125, Butterworths, Durban, 1973.

- Bauer, J., Was heisst Leben? Was ist lebendig, was beseelt? In Salzburger Jahrbuch fur Philosophie, 1970, 275, Pustet,

Salzburg.

- Ibid, 127

- See Landman, W. A. and Roos, S. G., op. cit., 121-123.

- See:

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., Liebenberg, C. R., Opvoedkunde en Opvoedingsleer vir Beginners, Chapters 5 and 6. University Publishers and booksellers, Stellenbosch, 1971

- Landman, W. A., Leesboek vir die Christen-Opvoeder, 89-106. N. G. Kerkboekhandel, Pretoria, Third expanded edition,

1974

- Brand, G., Die Lebenswelt. 383-386. W. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1971.

- See:

- Landman, W. A. and Roos, S. G., op. cit., Chapters 3 and 4.

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., van Rooyen, R. P., Die Praktykwording van die Fundamentele Pedagogiek, Chapters 1, 2, 4

and 7.

- See: Landman, W. A., Kilian, C. J. G., Leesboek vir die Opvoedkunde student en onderwyer, 87-88. Juta and Kie,

Johannesburg, 1972

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., op. cit., Chapter 4. See section headings: Explanation of the first and second movements

and integrated synthesis

- Bohm, R., Vom Gesichtpunt der Phaenomenologie, 220-223. M. Nijhoff, The Hague, 1968

- de Boer, Th., De Ontwikkelingsgang in het denken van Husserl, 449-450. Van Gorcum, Assen, 1966

- Schutz, A., Collected Papers III, 30-32. M. Nijhoff, The Hague, 1970.

- Landman, W. A. Kommentaar: Die Perspektief-idee in South African Journal of Pedagogy, Dec. 1973.

- Heidegger, M., Nietzsche I, 67, Neske, Pfullingen, 1961.

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., van Rooyen, R. P., op. cit., Chapter 4.

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., Liebenberg, C. R., op. cit., 26

- See Landman, W. A. and Roos, S. G., op. cit., Chapter 4.

- Gadamer, H-G, Wahrheit und Methode, 62-66. Mohr, Tubingen, 1965.

- Landman, W. A., Kilian, C. J. G., Roos, S. G., Denkwyses in die Opvoedkunde, 12-13. N. G. Kerkboekhandel, Second expanded edition, Pretoria, 1974

- Levinas, E., Totaliteit en het Oneindige, 102. Lemniscaat, Rotterdam, 1961/66

- Landman, W. A. and Roos, S. G., op. cit., Chapter 4.

- de Tollenaere, M., Lichaam en Wereld, 104-107, 109-111. Desclee de Brouwer, Utrecht, 1967

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., van Rooyen, R. P., op. cit., section [1.4]

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., Liebenberg, C. R., op. cit., 22-23, 69-70

- Hartmann, N., Ethics I, 41, 66-69, 86-87, 100-102, 114, 146, 170-178, 196-199; II, 130, 133; III, 19, 186-187

- Landman, W. A., Roos, S. G., Liebenberg, C. R., op. cit., 82-83

- Lesnoff-Caravaglia, G., Education as Existential Possibility, Chapter 2. Philosophical Library, New York, 1972

- Seiffert, H., Erziehungswissenschaft im Umrisz, 69-84, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1969

- Xochellis, P., Paedagogische Grundbegriffe, 15, 48n, 58, 63, 113. Ehrenwirth, Munich, 1973

- Strasser, S., Opvoedingswetenschap en Opvoedingdwijsheid, 30-41. Malmberg, 'S-Hertogenbosch. Third edition, 1965.

- Rombach, H., Strukurontologie, 81-85, 88-89, 101-102, 135, 161, 270. Alber, Freiburg, 1971

- See Hengstenberg, H-E, Freiheit und Seinordnung, 239. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1961

- Warnach, V., Satzereignis und Personale Existenz in Salzburger Jahrbuch fur Philosophie, X/XI, 96-97. A. Pustet,

Salzburg, 1966/67

- Ibid, 97-98

- Gabriel, L., Sinn und Wahrheit in Wisser, R. (ed.), Sinn und Sein, 136, Max Niemeyer, Tubingen, 1960

* These three terms are placed between brackets because here one

really has to do with a tautology.

** Note that anthropology, anthropologist, etc. refer to philosophical anthropology and not to

the social science.